Ensuring safety in aviation is paramount, and SAFA Ramp Inspection is a vital safety assessment program for foreign operators to monitor safety compliance through ramp inspections on their aircraft.

In this guide, we will explore why SAFA ramp inspections are vital, who is responsible for conducting them, what tools and checklists are used, and how findings are addressed. By the end of this post, you will have a complete understanding of the process and importance of SAFA ramp inspections in maintaining aviation safety.

The substantial growth in air travel has created a major challenge for many countries in ensuring their airlines comply with ICAO requirements as per the Chicago Convention. To maintain confidence in the aviation system and protect the interests of European citizens living near airports or traveling on third-country aircraft, the EU recognized the need to enforce international safety standards within its borders. This is accomplished through the implementation of ramp inspections on third-country aircraft landing at airports in EU member states.

“Third-country aircraft” is officially defined as an aircraft that does not operate under the authority of a Member State within the European Community.

The Directive 2004/36/EC provides a harmonized approach for the effective enforcement of international safety standards within the European Community by standardizing the rules and procedures for ramp inspections of third-country aircraft landing at airports within the Member States.

Objectives and key benefits

The primary objective of a SAFA ramp inspection is to assess compliance with ICAO standards as per the Chicago Convention.

SAFA ramp inspections offer several key benefits:

- Improve aviation safety by identifying and fixing safety issues before they lead to accidents.

- Help to maintain public confidence in aviation.

- Promote fair competition in the airline industry.

- Promote global harmonization of safety standards.

What is SAFA

SAFA stands for Safety Assessment of Foreign Aircraft and is a vital program aimed at maintaining aviation safety standards.

The Safety Assessment of Foreign Aircraft (SAFA) program was launched in 1996 by the European Civil Aviation Conference (ECAC) to complement ICAO audits. It primarily involves on-site inspections of aircraft at airports, often known as ramp inspections, to ensure compliance with ICAO standards. The EU SAFA program is now contained within the EU Ramp Inspection Program.

Ramp Inspection Program

In 2012, The EU Ramp Inspection Program replaced the original EU SAFA Program and has two major components:

- SAFA ramp inspections – for third-country operators; and

- SACA ramp inspections – for community operators.

Operators licensed by EASA Participating States and inspected by other EASA Participating States are checked against EU Standards; those inspections are referred to as Safety Assessment of Community Aircraft (SACA) inspections. All other inspections use ICAO Standards and are commonly known as Safety Assessment of Foreign Aircraft (SAFA) inspections. In addition, each ICAO contracting State should perform ramp inspections on operators licensed by them, such inspections are called Safety Assessment of National Aircraft (SANA) inspections.

SACA vs. SAFA

SACA (Safety Assessment of Community Aircraft) ramp inspections: SACA ramp inspections performed by an EASA Member State on aircraft used by operators under the regulatory oversight of another EASA Member State. These inspections take EASA requirements which are at least equal, but often more stringent than ICAO standards as the regulatory reference.

SAFA (Safety Assessment of Foreign Aircraft) ramp inspections: SAFA ramp inspections performed by non-EASA Participating States on any aircraft and ramp inspections performed by EASA Participating States on an aircraft operated by an operator under the regulatory oversight of a non-EASA Member State. These inspections take ICAO standards as the regulatory reference.

Note: Non-EASA Participating States are all Non-EASA Member States that have entered into a working arrangement with EASA. You can find the current list of Participating States engaged in the EU Ramp Inspection Program on the EASA website.

EASA Responsibilities for RAMP Inspections Program

EASA is responsible for coordinating the RAMP inspections program. Its main tasks are:

- to manage the ramp inspection procedures.

- to collect the inspection reports from the Participating States engaged in the program.

- to develop, maintain, and continuously update the centralized database holding the inspection reports.

- analyze the database content and other relevant information concerning the safety of aircraft and its operators.

- based on the analysis, report potential aviation safety issues to all the Participating States and the European Commission to maintain an operator priority list for ramp inspections.

- to conduct standardization visits to the Participating States.

- to assess the harmonized implementation of the program.

Who Does the SAFA Inspections and How

SAFA ramp inspections are conducted by authorized inspectors. These inspections are generally unannounced and can be conducted at any time of the day or night.

Inspection covers various aspects, such as pilot licenses, onboard documents, compliance with procedures by flight and cabin crew, safety and emergency equipment, onboard cargo, and the technical condition of the aircraft is assessed through maintenance records and physical inspection.

Explore: How to become a SAFA Ramp Inspector?

A ramp inspection can be started as soon as practicable, such as when the aircraft is fully parked and its on the chock, with engines shut down, and anti-collision lights turned off. Usually, two inspectors come to inspect the aircraft, and the tasks can be divided between them.

Before commencing a ramp inspection, inspectors usually introduce themselves to the pilot-in-command of the aircraft or, in their absence, to a member of the flight crew or the most senior representative of the operator. When it is not possible to inform any operator representative, or when no such representative is present in or near the aircraft, the general practice should be to wait until such a representative becomes available. However, in such cases, the exterior inspection of the aircraft may be conducted before the representative arrives at the aircraft.

The inspector will inform (where applicable) staff of possible hindrances due to the inspection task.

Any unnecessary contact with passengers should be avoided by inspectors and the inspection should not interfere with the normal boarding/disembarking procedures.

Oversight authorities of the Member States engaged in the SAFA Program choose which aircraft to inspect. Some authorities carry out random inspections while others try to target aircraft or airlines that they suspect may not comply with ICAO standards.

When the flight crew doesn’t cooperate or refuses an inspection without a valid reason, the competent authority should consider preventing the aircraft from taking off. In such cases, the responsible authority must inform the operator’s competent authority as soon as possible. A safety report could be filed to inform the Participating States. Valid reasons to allow the operator to depart without an inspection, unless there are clear safety concerns, may include:

- The aircraft is ready to depart with passengers on board.

- It’s an outbound emergency medical flight.

To ensure the harmonization and standardization of SAFA Ramp Inspections, the guidance materials on SAFA Ramp Inspections offer clear instructions to inspectors conducting these inspections. These guidelines are primarily based on Standard and Recommended Practices (SARPs) defined by the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO).

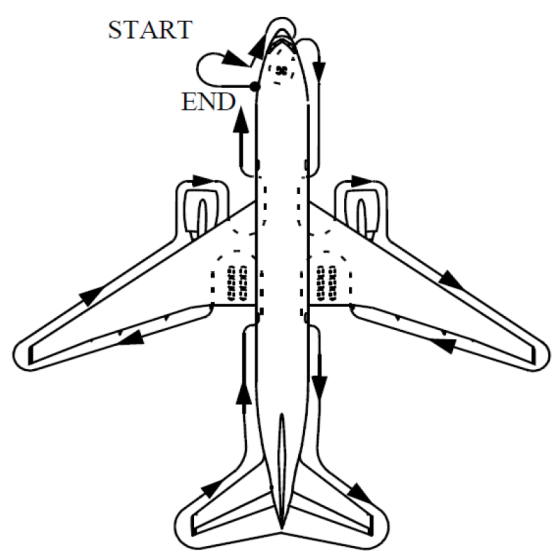

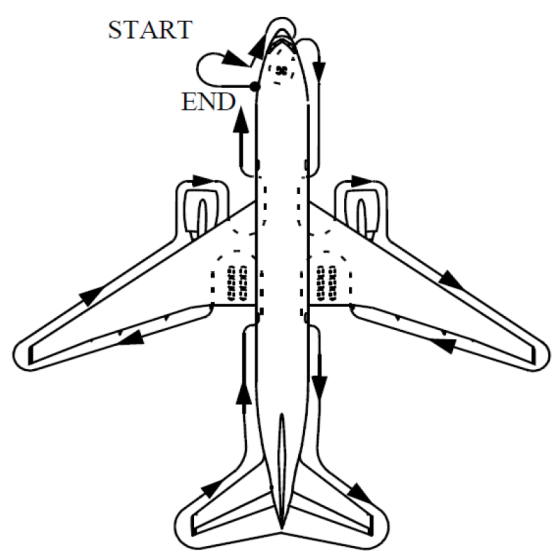

Walk-around inspection

An aircraft inspection should stay within the standard scope of a walk-around inspection. Inspection tools, such as cameras, should be used solely for gathering evidence. Opening access panels and wheel well bay doors is prohibited unless it becomes necessary to trace the source of a leak, in which case it should only be done after consultation with and assistance from the crew.

A standard walk-around inspection is described below and should generally be completed in no more than 10-15 minutes for narrow-body aircraft and a maximum of 20-25 minutes for larger wide-body aircraft.

SAFA Ramp Inspection Checklist

SAFA inspectors use a standardized checklist encompassing 53 inspection items during ramp checks.

Explore: SAFA Checklist: Key Areas To Focus

The ramp inspection checklist contains 53 items. Of these,

- A-items: these are the 24 items related to operational requirements to be checked on the flight crew compartment.

- A01: General Condition

- A02: Emergency Exit

- A03: Equipment

- A04: Manuals

- A05: Checklists

- A06: Radio Navigation Charts

- A07: Minimum Equipment List

- A08: Certificate of Registration

- A09: Noise Certificate

- A10: AOC or equivalent

- A11: Radio Licence

- A12: Certificate of Airworthiness

- A13: Flight Preparation

- A14: Weight and Balance sheet

- A15: Hand Fire Extinguishers

- A16: Life jackets/flotation device

- A17: Harness

- A18: Oxygen equipment

- A19: Flash light

- A20: Flight Crew Licence

- A21: Journey Log Book, or equivalent

- A22: Maintenance Release

- A23: Defect notification and rectification (incl. Tech Log)

- A24: Pre-flight Inspection

- B-items: these are the 14 items that address safety and cabin items.

- B01: General Internal Condition

- B02: Cabin Attendant’s Station/Crew Rest Area

- B03: First Aid Kit / Emergency Medical Kit

- B04: Hand Fire extinguishers

- B05: Life jackets / Flotation devices

- B06: Seat belt and seat condition

- B07: Emergency exit, lighting and marking, Torches

- B08: Slides/Life-Rafts (as required), ELT

- B09: Oxygen Supply

- B10: Safety Instructions

- B11: Cabin crew members

- B12: Access to emergency exits

- B13: Safety of passenger baggage

- B14: Seat capacity

- C-items: these are the 12 items concerning the aircraft condition.

- C01: General external condition

- C02: Doors and hatches

- C03: Flight controls

- C04: Wheels, tyres and brakes

- C05: Undercarriage, skids/floats

- C06: Wheel well

- C07: Powerplant and pylon

- C08: Fan blades

- C09: Propellers, rotors (main/tail)

- C10: Obvious repairs

- C11: Obvious unrepaired damage

- C12: Leakage

- D-items: these are the 3 items related to the inspection of cargo (including dangerous goods) and the cargo compartment.

- D01: General condition of cargo compartment

- D02: Dangerous Goods

- D03: Safety of cargo on board

- E-items: In case any general inspection items are not addressed by the other items of the checklist, they may be administered by the E-item (General) of the checklist.

- E01: General

If you would like to learn more about each item on the checklist and get details about what inspectors actually check, please refer to the comprehensive SAFA checklist.

When there isn’t enough time or enough manpower to check everything on the checklist, inspectors should focus on the items they believe are most important for safety based on their training and experience. For example, a noise certificate is not as important to safety as ensuring that mass and balance documents are filled out correctly and calculations are accurate. The previous ramp inspection results and the age of the aircraft should also be taken into consideration.

Ramp inspectors should understand the key differences between SAFA and SACA inspections. For example, they should be aware that ICAO SARP does not mandate carrying NOTAM on board, but does require flight crew awareness of details relevant to the flight. While EASA regulation requires the NOTAM to be carried on board (electronic versions are allowed).

Ramp inspector’s privileges

SAFA Ramp Inspector’s privileges refer to the specific inspection tasks that a SAFA Ramp Inspector is authorized to perform. These privileges are determined based on the inspector’s training, experience, and qualifications, typically including their background as a commercial pilot license/airline transport pilot license (CPL/ATPL) holder, an aircraft maintenance engineer license (AML) holder, or a cabin attendant.

A Ramp Inspector can be a CPL/ATPL holder, an AML holder, or a cabin attendant. Former cabin crew may require additional training on cabin-related MEL items before they are considered qualified to inspect safety items in the cabin.

- CPL/ATPL holder is qualified to perform inspections on:

- A items

- B items

- C items

- D1/D3 items

- AML holder is qualified to perform inspections on:

- A items except for A13, A14

- B items

- C items

- D1, D3 items

- Cabin attendant is qualified to perform inspections on:

- A15-A19

- B items

Possibility of flight delay

It is the SAFA ramp inspections program policy not to delay an aircraft except for safety reasons.

A delay of the flight might be justified for safety reasons, such as whenever non-compliances are detected and either need a corrective action before departure or need proper identification/assessment by the operator, for example, if:

- Tyres appear to be worn beyond the limits;

- Oil leakage is to be checked against the applicable AMM to determine the actual limit;

- A flight crew member cannot produce a valid license. Clarification is to be sought from the operator and/or NAA to confirm that the flight crew member has a valid license by requesting, for instance, a copy of the license to be sent to the inspectors for verification;

- Relevant flight operational data are missing (e.g. missing or incorrect performance calculation, incorrect operational flight plan, incorrect weight and balance calculation); or

- Damages, being assessed as having a Major influence on flight safety, are identified.

Alcohol Tests

Alcohol tests should be carried out only on flight crew and cabin crew assigned operational duty, during ramp inspection. As per the ramp inspection manual, an Alcohol test should be preferably carried out at the beginning of the ramp inspection.

- Test result negative: when the breath alcohol concentration (BrAC) measured by a breath alcohol tester is lower or equal to 0.2 grams of blood alcohol concentration (BAC) per liter of blood, or the national statutory limit, whichever is lower.

- Test result positive: when the breath alcohol concentration (BrAC) measured by a breath alcohol tester is higher than 0.2 grams of blood alcohol concentration (BAC) per liter of blood, or the national statutory limit, whichever is lower.

The alcohol test involves two parts: an initial test and a confirmation test when the initial result is positive. If both tests show positive results, it’s considered a CAT 3 finding. There should be at least a 15-minute waiting period between the initial and confirmation tests. During this time, the crew remains on duty, but inspectors must make sure they don’t eat, drink, or put anything in their mouths to prevent any residual alcohol from affecting the confirmation test. If a crew member doesn’t cooperate during this waiting time, it’s treated as a positive result.

The confirmation test should be performed at least 15 minutes but not more than 30 minutes after the completion of the initial test.

In case of a positive confirmation test, a CAT 3 finding should be raised under item E01.

Each State is entitled to decide the way alcohol testing will be carried out. Alcohol testing is fully integrated in the EU Ramp Inspection Program and performed by ramp inspectors or by other officials being part of the inspection team, or stand-alone alcohol testing managed and performed by other officials.

Understanding Findings

A finding is a non-compliance with the relevant standards. For each inspection item, 3 categories of possible deviations from the standards have been defined. The findings are categorized according to the perceived influence on flight safety.

The three categories of findings are as follows:

- Category 1 is a minor finding and it is considered to have a minor influence on safety.

- Category 2 is a significant finding and it suggests a significant influence on safety.

- Category 3 is a major finding and this signifies a major influence on safety.

When considering the findings established during a ramp inspection, Category 2 (significant) and Category 3 (major) findings require the highest attention when it comes to the need for rectification.

It is important to note that any other safety-relevant issues identified during a SAFA inspection, although not constituting any findings, can be reported as General Remarks (Cat G) under the relevant inspection item. For example: missing life jackets for flights conducted entirely overland; or an electrical torch is missing or unserviceable during a flight conducted entirely in daylight.

The findings should be categorized according to the list of PDFs. In the SAFA PDF list, the description, categorization, and reference to the applicable standard are given. Although the list of PDFs is as complete as possible, it cannot cover all possible deviations that may occur. The SAFA PDF list is intended to be used by the inspector to guarantee a common description and categorization of findings.

In those cases where there is no appropriate PDF, the inspector should, based on his proficiency and the impact on aviation safety, make a sound judgement into which category the finding needs to be placed. The ramp inspection tool allows findings to be entered by the user, these findings are called User-Described Findings (UDFs). These UDFs will be monitored by EASA periodically and after evaluation may become part of the existing PDF list. Therefore the PDF list will be updated periodically.

Technical Defects (Airworthiness Findings)

- Minor defects are typically with minor influence on safety and should therefore be brought to the attention of the operator using a Category 1 finding.

- Significant defects are those defects, which are potentially out of limits and a further assessment may be needed to determine if the significant defect is within or outside the applicable limits. These defects should be recorded as Category 2 findings.

- Major defects are those defects which are out of limits. A Category 3 finding against manufacturer standards should always be demonstrated in relation to the operator’s aircraft technical documentation such as AMM, SRM, CDL, WDM, etc., and MEL references. In the absence of clear manufacturer standards, inspectors should only raise findings if their expert judgement (possibly supported by a licensed maintenance engineer) is such that similar circumstances on comparable aircraft would be considered to be out of limits.

Please note that “defects within limits, but not detected or recorded” should not be considered technical non-compliance.

Actions Following a SAFA Ramp Inspection

Following a SAFA ramp inspection, specific actions are taken based on the results of the inspection and the categorization of findings. These actions are important to maintain aviation safety and ensure compliance with international standards. There are three classes of action: class 1, class 2, and class 3.

Class 1 action: information to the captain

After each SAFA inspection, Class 1 action is mandatory, which involves sharing information about the results of the inspection, regardless of whether any findings were identified or not. This includes a verbal debriefing and the issuance of the Proof of Inspection (POI) to the aircraft pilot-in-command. In cases where the pilot-in-command is unavailable, another member of the flight crew or the operator’s most senior representative will receive this information.

Class 2 action: Information to the authority and the operator

Category 2 and 3 findings, which are considered critical and major safety concerns, require written communication. This communication ensures that both aviation authorities and operators are aware of these important issues.

Class 3 actions: Restrictions or corrective actions

A class 3 action follows a category 3 finding which is considered to have a potential major effect on the safe operation of the aircraft. This requires that corrective actions need to be taken by the operator before flight.

The class 3 action is further divided into 4 sub-actions:

- Class 3a: Restriction on the aircraft flight operation – Like restrictions on flight altitudes if oxygen system deficiencies have been found, a non-revenue flight to the home base if allowed for by the MEL, some seats that may not be used by passengers, and a cargo area that may not be used.

- Class 3b: Corrective actions before flight – Like temporary repairs to defects as per AMM, recalculation of mass and balance, a copy of missing documents to be sent by fax or email, and proper restraining of cargo.

- Class 3c: Aircraft detained by inspecting National Aviation Authority – The aircraft has to be kept ‘grounded’ until the safety hazard is removed. This class of action will only be implemented if the crew has refused to take the necessary corrective action. Additionally, class 3c action would be appropriate where an operator refuses to permit the performance of a SAFA inspection without a valid reason.

- Class 3d: Immediate operating ban – The competent authority may impose an operating ban on an operator or an aircraft in case of an immediate and obvious safety hazard.

Ramp Inspection Tool

The Ramp inspection tool is the backbone of the Ramp Inspection Program. It is the centralized database which is managed and maintained by EASA.

Each participating state uploads its reports to this tool, making them accessible to all other states. The information in the database is confidential and shared only with other participating states; It is not accessible to the general public. The database can be accessed through a web-based application by all aviation authorities of the participating states.

Operators and their Aviation Authorities (NAAs) can register online to that database; obviously, the access is limited to ramp inspection reports on their own aircraft. Since the user management is delegated to the local Aviation Authorities, these authorities need to have obtained access to the database before the operators can register themselves. Once the operator and/or the NAA has access, any follow-up information on the inspection can be uploaded to the database; this lowers the burden of the administrative workload considerably.

What are the PDFs

PDFs stand for Pre-Described Findings. They are a standardized set of descriptions used to categorize and report findings identified during the inspection process. Each PDF includes a detailed description of the finding, its categorization (Class 1, 2, or 3), and the applicable reference to the relevant ICAO or EASA standard. This information provides inspectors with a clear framework for documenting findings and allows for easy interpretation of inspection reports by aviation authorities and operators. The list of PDFs is periodically updated to reflect changes in regulations and to incorporate new safety concerns.

There is a unique identifier that is assigned to each Pre-Described Finding (PDF). This code is called a PDF code and is used to track the finding and to associate it with the relevant inspection report. You can find this code in the PDF list.

How to minimize SAFA findings

Minimizing SAFA findings is crucial for maintaining aviation safety and compliance. To minimize SAFA findings, it’s essential to maintain a proactive approach to aircraft maintenance and adherence to international safety standards.

Here are some effective strategies to minimize SAFA findings:

- Establish an effective Safety Management System (SMS): An effective SMS provides a framework for identifying, assessing, and managing safety risks. Include clear procedures for reporting, investigating, and implementing corrective actions on safety hazards. Establish a system that allows people to report anonymously.

- Provide adequate training for crew: Provide your crew members with comprehensive training on all relevant safety procedures and regulations. Tailor training to specific roles and responsibilities and cover specific areas that are sensitive to SAFA findings. Use refresher courses to regularly update your crew’s knowledge.

- Maintain accurate and up-to-date documentation: Keep all necessary documents, such as release certificates, maintenance records, and operational documents, readily available and up to date. Make sure documents are accessible to inspectors.

- Conduct regular Internal Audits: Regularly conduct internal audits to identify potential safety hazards and areas for improvement before they lead to SAFA findings.

- Learn from previous SAFA findings: Regularly review previous SAFA findings to identify recurring issues and implement corrective actions. Use this as feedback to improve your safety management system and overall safety performance.

- Conduct thorough pre-flight inspections: Ensure that pre-flight checks are consistently performed, including a walk-around inspection to identify any potential defects or irregularities. These inspections should be conducted by qualified personnel using standardized checklists.

- Conduct proactive maintenance: Implement a proactive maintenance program that emphasizes preventive maintenance and regular inspections. This will help to identify and resolve potential problems before they lead to SAFA findings. Integrate SAFA findings into the weekly maintenance schedule.

- Maintain a high standard of aircraft maintenance: Implement a comprehensive aircraft maintenance program that adheres to all applicable regulations and manufacturer recommendations. Regular maintenance can help to prevent aircraft defects and ensure that aircraft are airworthy. Make procedures to strictly follow maintenance instructions. Establish zero-tolerance policies.

- Prioritizing quality over speed: Allocate sufficient time to complete the task. Do not force your maintenance personnel to complete the task quickly. Allow them to take the required time (as per MPD) to accomplish the task efficiently and completely. This will significantly reduce the possibility of findings.

- Develop strong SOPs: Developing and implementing Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs) can significantly help minimize common SAFA findings by providing clear and consistent guidelines for operational procedures.

- Promote a safety culture: Encourage a strong safety culture within the organization by emphasizing the importance of safety in all aspects of operations. Encourage open communication and reporting of safety concerns, and recognize employees for their contributions to safety.

- Stay informed about regulatory changes: Regularly review and update company procedures and training materials to reflect any changes in aviation safety regulations. Stay up to date on industry trends and best practices to ensure your organization is operating at the highest level of safety.

By implementing these strategies and taking specific actions to address common areas of SAFA findings, operators can significantly minimize SAFA findings and improve their overall safety performance.